01: WHAT IS FOOD INSECURITY

Food insecurity is the inability to comfortably

access affordable, healthy dietary options.

In the context of New York City, it takes two forms:

proximity to healthy food options and also

cannot afford it

physical proximity to healthy food options,

but populace has difficulty affording it

On the contrary, there's also:

proximity to healthy food options and where populace

can afford it

In incumbent investigations by the USDA, food insecurity

is mostly emphasized by the lack of physical proximity

(10 mile radius) to a supermarket. However, since NYC

is so dense, the term "food swamp" must be used to discuss the

lack of economical access to healthier options. In order

to truly discuss which neighborhoods are riddled with

food insecurity, various investigations and correlations

of data such as income, supermarket and bodega counts,

median rent and vehicle counts are all correlated to

paint NYC's food insecurity landscape.

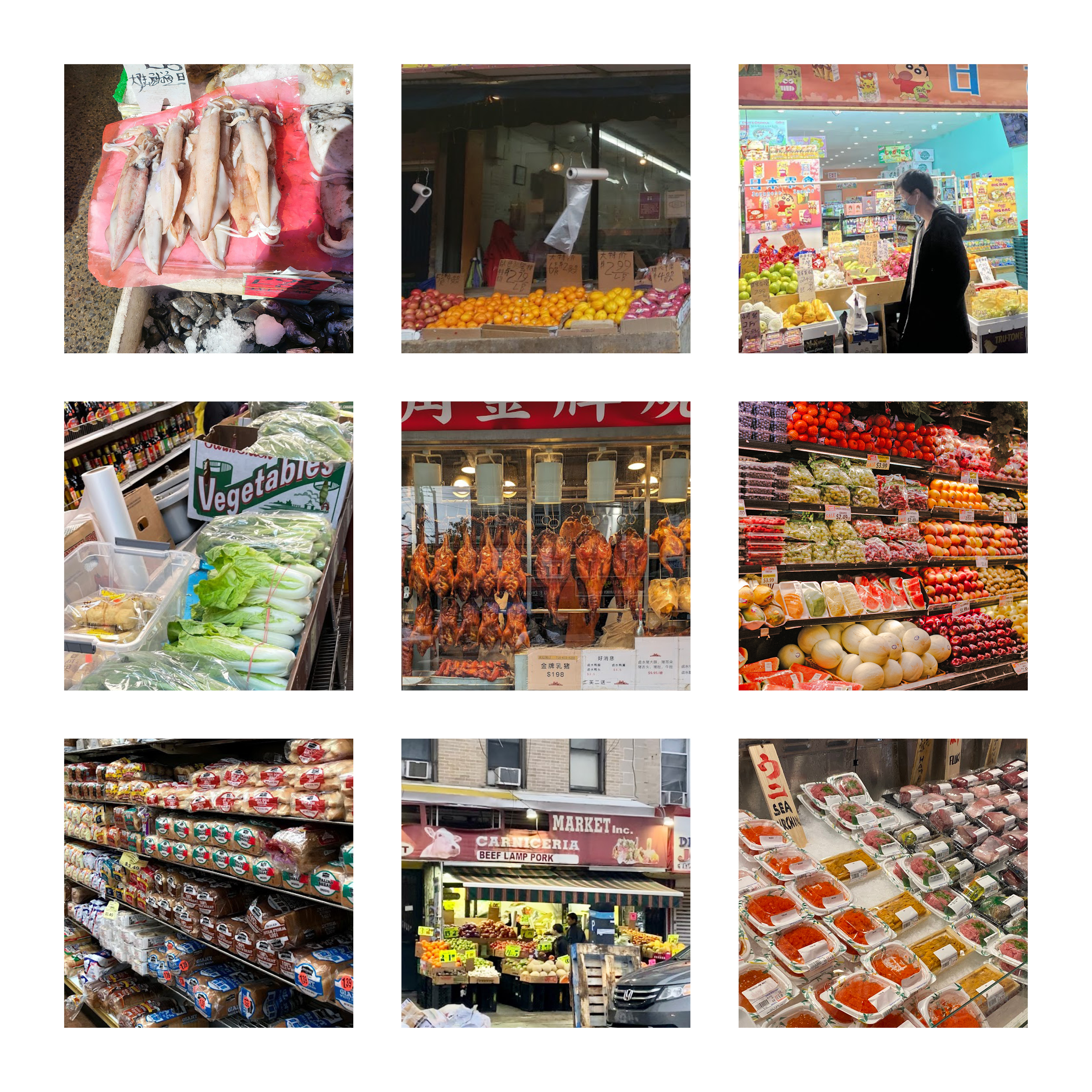

Matrix of street views showing a food desert (left), swamp (center) and oasis (right).

Though this will be looked into further, this gives an idea of infrastructural differences

between the three environments.

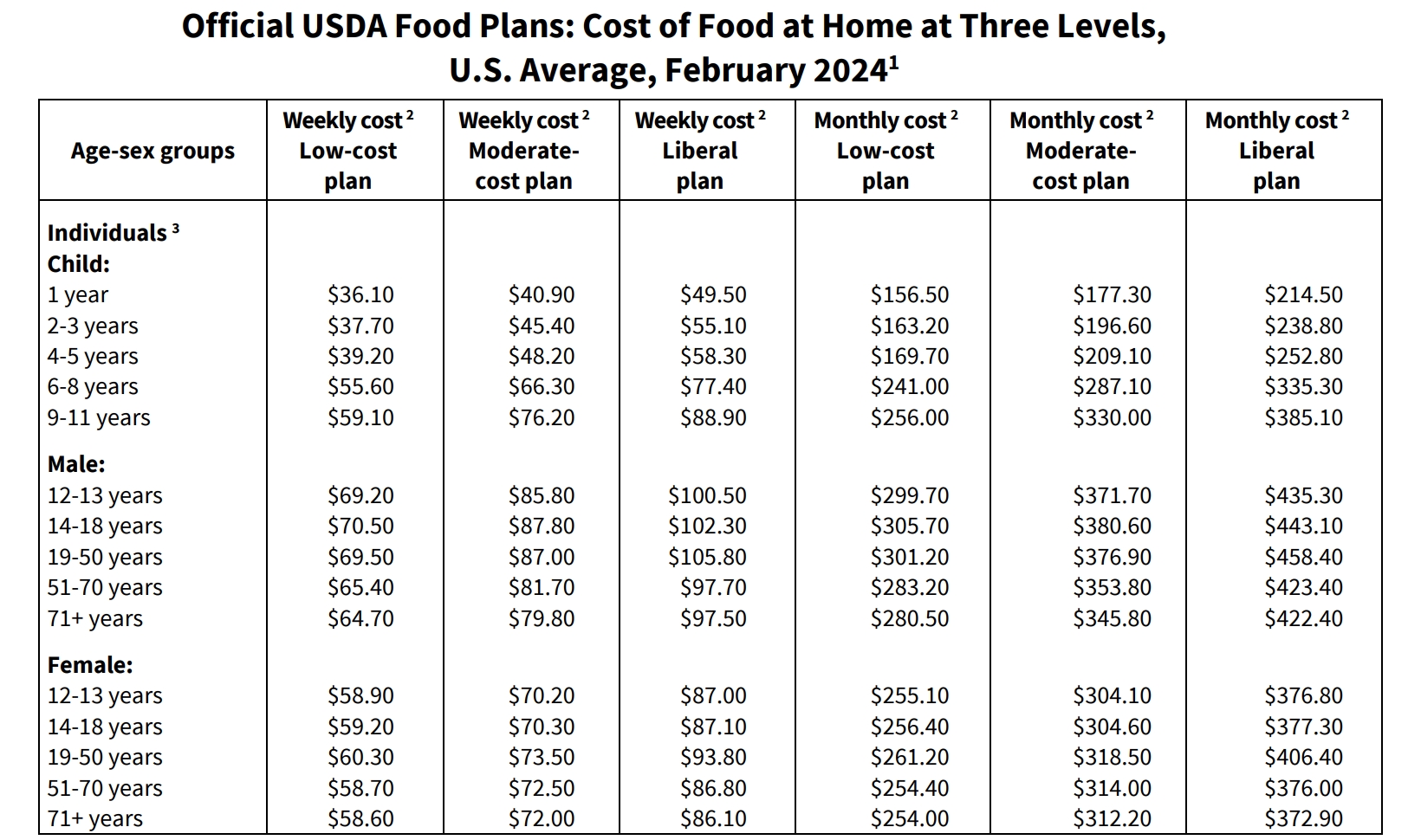

USDA Table showing recommended costs for healthy, nutritious meals per person.